Isolation and invisibility frame the challenges of Midwest AAS programs

Conditions of Success: The Asian American Studies Social Movement in the Midwest, 1990 - 2009

Stephanie T.X. Nguyen, 2017

- Table of Contents

- Abstract

- The Birth of Asian American Studies

- Regional Barriers for Asian American Studies in the Midwest

- “Over-represented” yet “Neglected” Minorities: The Racial Climate and Institutional Barriers for Asian Americans at IUB from 1980s-2000s

- Twenty years of Activism: IUB’s Asian American Social Movement

- 1990-1996: Building “Asian American Consciousness”

- 1996-1999: Gaining Critical Mass through Asian Pan-Ethnicity and Cross-Racial Collaborations

- 2000-2009: Deradicalization of Asian American Studies

- Conclusion

- References

Abstract

This historical case study at Indiana University (IUB), in the years 1990 to 2009, explores how the Asian American Studies (AAS) movement gained traction in the Midwest. This paper examines how activists initiated an academic curricular change despite a small critical mass of activists, political passivity, institutional racism and bureaucracy. Activists’ efforts spanned 20 years starting with a student-led initiative and culminating into multi-level and cross-racial alliances with faculty, staff, and other ethnic organizations on campus to intellectualize the need for an AAS program within a traditional curriculum offering. Findings from this paper continues the effort to document Asian American education history beyond the West Coast and the study of social movements as a mode of change within postsecondary institutions.

On November 5, 2001, six faculty members, one graduate student, and one IUB administrator submitted a proposal to the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, the university chancellor, and the vice president for student development and diversity to create an Asian American Studies (AAS) program at Indiana University Bloomington (IUB). However, these demands for an AAS program started in the 1980s amidst a campus climate that was considered unwelcoming and not inclusive of Asian Americans at IUB. Asian American activists spent almost 20 years not only advocating for an AAS program, but to be seen and recognized by the IUB administration as a minority student population. But why did it take Asian American activists so long to achieve their social movement goals? This historical analysis examines the complicated mix of national, regional, and institutional barriers that elongated the achievement of these social movement outcomes. It also examines how IUB’s AAS social movement is interconnected with decades of activist history starting from the national movement for ethnic studies from the late 1960s, the regional advocacy for Midwest AAS programs in the 1990s, and culminating to the IUB advocacy efforts of students, faculty, and staff from the 1990s to 2000s. This paper focuses on the following research questions:

- What were the regional and institutional barriers that made it challenging for the activists to attain their goal of developing an AAS program?

- Why did Asian American activists demand for an AAS program?

- What were the conditions of success that helped activists to overcome these barriers and attain their movement outcomes of developing an AAS program at this large, public and predominantly white institution?

To address these questions, I draw from social movement research as a mode of change within an organizational structure. Social movements are a type of group action that mount to effective challenges and resist the dominant culture within an organization or society.1 They carry out social change sometimes in informal or even formal groups of people or organizations.1 Social movement research concludes that social change does not emerge from a vacuum, and individuals do not automatically act together to instigate change. Rather social movements emerge from years of planning and debate among the aggrieved.2 Activists must create and exploit opportunities for social change, even the most organized and highly motivated groups find it difficult to change social practice.2 Movements often need political opportunities and substantial level of internal development.

Using this social movement framework, this paper is a historical case study of IUB, in the years 1990 to 2009, that examines the conditions of successful adoption of an AAS program at a predominantly white public university in the Midwest. It examines how actors within a highly structured administration instigated an academic curricular change despite looming barriers such as a small critical mass of activists, political passivity, institutional racism, and institutional bureaucracy. I argue that conditions were successful because of three key strategies: (1) rich cultural programming that unified the Asian American student community; (2) cross-racial collaborations to gain a critical mass of activists; and (3) deradicalization of Asian American ethnic demands to intellectualize the need for an AAS program.

This paper is significant in two areas of literature. First, it continues the call to further document the history and perspectives of Asian Americans beyond the West Coast.3 In 2009, Asian American scholars published a special issue in the Journal of Asian American Studies to reframe the mission and the teaching of AAS in the Midwest, a region that is seen as isolating and racially homogenous to Asian Americans. The authors4, 5, 6 asked for continued research on examining the Asian American experience within a perceptively white region and context. Within Asian American scholarship, this case study examines what isolationism and invisibility looks like for Midwest Asian Americans. It also complicates AAS scholarship: it demonstrates how institutional context and geography has an effect on the Asian American identity, political participation, and self-perception.

This case study also continues the call from historian Eileen Tamura7 to document and understand the educational history of Asian Americans. Specifically, this case study complicates the traditional image of education at a university. This case study recognizes the power of informal education, one that did not come from a traditional classroom rather from student-initiated social and academic programming. When the university did not offer a curriculum that reflected the relevant history of minority groups on campus, Asian American activists created their own cultural programming to learn about Asian American history, literature, and political identity. Students created a community and environment where they learned from each other, invited outside speakers to come to campus, and held discussions to examine Asian American stereotypes.

Second, this paper adds to higher education organizational literature to understand social movements as a mode of change. The academic system is often changed by social movements such as the ethnic studies movement of the 1960s that led to new academic programs.8, 9 This case study also complicates how decisions are made within a multi-level higher education institution. Specifically, this paper examines an emerging pattern on how diversity issues are generated at the student-level, and how they move up into higher decision-making levels10 suggesting a reactive versus proactive approach to addressing campus climate. Activists used non-disruptive strategies such as educational programming and coalition-building to convince administrators to listen to their cause. I also argue that institutions are unique and not all tactics within one social movement will work for others. However, this case study continues to add to social movement literature by identifying common patterns of social change within the higher education institutional context.

This paper begins with an introduction to the AAS social movement that emerged from Third World Strike of 1968-1969 advocating for ethnic studies programs within the higher education curriculum. It then introduces the AAS movement within the Midwest, outlining the regional barriers particularly isolation and invisibility that activists faced when creating an AAS program in their institutions. Within the context of the AAS movement in the Midwest, the second part of this paper examines the racial climate for Asian Americans at IUB and the institutional barriers they faced in the 1980s through 2000s. The second part of the paper discusses how Asian American activists reached their social movement goals despite these regional and institutional barriers. As early as the 1990s, Asian American activists formed student organizations and clubs to learn about what it means to be Asian American within a predominantly white university. By the mid-1990s, these student organizations had grown into a pan-ethnic and multi-racial interconnected network to unify around social change. By the late 1990s, activists were able to successfully attain as AAS program because of cross-racial collaboration and intellectualizing the argument for such a program.

The Birth of Asian American Studies

AAS was created from the efforts of white and minority activists who marched and picketed fornearly five months between 1968-1969 at San Francisco State College.11 Named the Third World Strike of 1968-1969, students, faculty and community members made national headlines as they took over university buildings and clashed with the police to demand equal access to public higher education, more senior faculty of color, and the creation of ethnic studies programs.12 The strike was successful because of the large critical mass of activists and cross-racial collaborations that supported the outcomes of the movement. Alongside ethnic and political community organizations, African American, Asian American, Chicano, Latino, and Native American students united to fight for the redefinition of education that should be relevant and service the needs of the communities.13 Community organizations assisted student organizations by teaching students about political consciousness and educating them about their ethnic histories.2 Specifically, Asian American student groups had st rong ties to community organizations that taught Asian American students effective strategies of resistance, fund-raising, and support for picketing activities.13 From these pan-Asian and cross-racial efforts, the Third World Strike of 1968-1969 eventually achieved their social movement through the establishment of the School of Ethnic Studies.14 AAS grew from this famous social movement with 439 colleges in the country offering a total of 8,805 ethnic studies courses by 1978.11

Within ethnic studies, AAS is an institutionalized field in higher education with an academic endeavor with a mission to address the needs of Asian American students and transform racially unjust aspects of American society.15 More specifically, AAS is the documentation and interpretation of the history, identity, social formation, contributions, and contemporary concerns of Asian Americans and their communities within the American context.12 AAS research, teaching and curriculum development relate to the experience of Asian American with a strong focus on community issues and social problems.12

Regional Barriers for Asian American Studies in the Midwest

AAS programs first developed in higher education institutions on the West Coast in the 1960s-1970s and spread to institutions the Midwest and the East Coast by the 1980s-1990s.5 Unlike West Coast higher education institutions that had a large Asian American student population, the student demographics as well as sociopolitical and racial politics differed in institutions “East of California.”5 In an attempt to redefine AAS from its California origins, representatives from 23 colleges and universities in 1991 gathered at Cornell University to establish the “East of California” (EOC) caucus of the Association for Asian American Studies.5 The EOC caucus explored alternate ways to teach, research, fundraise, and build programs that focused on less-studied Asian American ethnic groups such as Filipino, South Asian, and Southeast Asian Americans living in EOC regions.5

AAS scholars in the Midwest refined the regional differences during a meeting of twelve Big Ten institutions in 2006 in Chicago.24 The Committee on Institutional Cooperation (CIC)* was a conglomeration of 12 research universities at thirteen campuses: the University of Chicago, the University of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign and Chicago campuses), Indiana University, the University of Iowa, the University of Michigan, Michigan State University, the University of Minnesota, Northwestern University, the Ohio State University, Pennsylvania State University, Purdue University, and the University of Wisconsin-Madison.6 Between the 1990s and 2000s, eleven out of the 13 institutions had an AAS program.

*The CIC is currently renamed to the Big Ten Academic Alliance.

The CIC collaborative recognized that Midwest AAS programs share similar challenges that fledging West Coast AAS programs experienced in the 1960s-1970s. These similarities included programs founded through activism, limited resources across different institutions, and gross misconceptions about Asian Americans. Even though each CIC AAS program differed in size, structure, agenda, autonomy, and scope, most if not all, had share similar histories of creation.5 Like their West Coast counterparts, the institutionalization of Midwest AAS programs relied on years, even decades, of activism from faculty, staff, and students.5 Midwest AAS programs faced uneven institutional support across multiple institutions. For example, some Midwest AAS programs only offered single or irregularly-occurring courses while other programs offered a variety of certifications including undergraduate minors, certificate programs, or undergraduate degrees.6 Finally, like their West Coast AAS programs, Asian American activists fought for the fought for the insertion of their history into the academy.13 AAS activists across the CIC campuses combatted rampant ignorance about Asian Americans and AAS programs.6 Often AAS programs were confused with East Asian studies, and Asian American faculty and students were misidentified as “international.”6

While acknowledging the similarities that Midwest AAS programs have with their West Coast counterparts, the 23 representatives at the CIC meeting met to discuss the institutional and the intellectual challenges of working in Midwest AAS programs.6 This meeting was important because scholars and practitioners acknowledged that geography has shaped the practice of AAS in the Midwest, and more scholarly attention is needed to understand the unique challenges in studying, teaching, researching, and engaging with Midwest Asian American populations.4

The paradigms of isolation and invisibility frame the challenges of Midwest AAS programs. The first paradigm, isolation, is defined by the unwelcoming image of the Midwest to Asian American students and faculty. Demographically, the U.S. Census Bureau defines the Midwest comprising of twelve states: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin.16 Out of the five geographic regions, the Midwest has the smallest proportion of Asian Americans living in the area.17 According to the 2010 Census, out of the 17.3 million Asian Americans in the U.S. about 11.3 percent of Asian Americans live in the Midwest.17 Some states, especially the urban areas Illinois, Minnesota, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin, have higher percentages of Asian Americans.5

Perceptually, the region, nicknamed the “Heartland” of America, is encompassed with a traditional “American” character of a supposed commitment to family values, individual rights, independent determination, and military pride.18 Compared with the cultural image and demographics of the coasts, the Midwest has a cultural image with a presumed white homogeneity in its vast rural areas and limited cosmopolitanism.18 The region’s presumed racial demographics and its cultural identity have contributed to its image as unwelcoming to Asian Americans.4

This unwelcoming image translates to a chilly campus climate for Asian American students and faculty at higher education institutions in the Midwest. Asian American faculty often faced intellectual isolation, defined as dissatisfaction with their physical distance from library archives, communities of color, and other scholars in their field. Sometimes, faculty were the only Asian Americans within their department. Other times, they were the only faculty member who was teaching AAS courses and felt pressure not only to teach but also to mentor the growing number of Asian American students in their university. In addition, faculty felt additional pressure to “teach diversity” not only to their students but also to colleagues and administrators.6 Faculty described the stress of carrying heavier service loads than their colleagues and defending research agendas to peers who were unfamiliar and sometimes hostile to racial and ethnic studies.6

Asian American students growing up in the Midwest report experiencing forms of isolationism that affects their self-perceptions and interactions with others. Most Asian American students reported growing up in predominantly white neighborhoods in the Midwest, and sometimes being the only one of a handful of students of color at school.14 Many if not all, reported facing negative stereotypes and perceptions of Asian Americans.14 By growing up in this pervasively white frame, Asian American students in the Midwest report that their self-perception was greatly influenced by how they are compared to their white classmates.14 Asian American students grappled with ethnic self-doubt (and sometimes reaching self-hate) while experiencing feelings of shame and inferiority compared to their white classmates.14

The second paradigm that frames unique challenges for Midwest AAS programs is invisibility, which is defined as little to no resources from Midwestern institutions and limited research focus by national AAS scholarship. At the institutional level, Midwest AAS advocates were frustrated with the invisibility in both the standard American history and their university administration despite being a significant proportion of the minority student population on campus.15 One of the first institutions to create a Midwest AAS, University of Wisconsin-Madison wrote in their program proposal that the Asian American student population was the largest racial group representing 2.2 percent of its student population.19 The University of Wisconsin-Madison committee argued, “Our understanding of race and ethnicity in American history will remain incomplete at best, and perhaps flawed, if scholars leave unattended the study of Asians in America.”19 Even though relatively small compared to the other parts of the U.S., the Asian American population in the Midwest is the second fastest growing in the U.S. in the last two decades at a 48 percent growth rate.17 This dramatic population growth reflected on Asian American student enrollment at Midwest higher education institutions.

Within the CIC, Asian American enrollment ranged from 2-23 percent of their student population in the 1990s.20 Despite these enrollment numbers, many Midwestern universities did not recognize Asian Americans as underrepresented minorities.20 For example, University of Illinois Chicago specifically did not categorize Asian American students as underrepresented minorities because “their undergraduate percentage in the undergraduate population is above their respective percentages in the state population.”20 Institutions such as Northwestern University granted Asian American students as “ethnic” minorities but were not considered “underrepresented” minorities on campus.20 Out of the 12 member institutions in the CIC, Purdue University was the only one that recognized Asian Americans as underserved minorities.20 Even when there are sizable populations of Asian Americans on campus, stripping Asian American students from their minority status is excluding them from the discussion of race as well as access to academic, financial, social, and cultural programming that are afforded to other students of color.5

Within the national AAS scholarship, the experiences and histories of Midwest Asian Americans were also invisible. Despite having lived, worked, and built communities in the Midwest since the late nineteenth century, scholars have critiqued that national AAS scholarship is “California-centric.”6 Curriculum structure and literature that were developed in West Coast AAS programs have little applicability to Asian Americans in the Midwest. Particularly Midwestern Asian Americans find it difficult to relate to historical events that occurred in the West Coast.5 Moreover, growing up in a largely white context, Midwestern Asian American students do not easily identify with the political, historical, and racial characteristics attached to the Asian American identity.21

This inability to understand what it means to be Asian American within a predominantly white region can be perceived as political passivity. The dangers of political passivity can be Asian Americans’ inability to defend themselves against discrimination and prejudice, possible damage to their selfperception, lack of experience to talk about and understand highly charged racial issues, and inability to engage in both their community and American political process.5, 14 Thus, scholars have not only argued for more research to understand the Asian American experiences in the Midwest but to entirely reframe the teaching and research of Midwest AAS programs as an integral part of the liberal arts education.4

“Over-represented” yet “Neglected” Minorities: The Racial Climate and Institutional Barriers for Asian Americans at IUB from 1980s-2000s

IUB Asian Americans activists faced the same two paradigms of invisibility and isolation on their own campus. Since the 1970s, Asian Americans were culturally acknowledged as minorities10 but institutional policies in the 1980s did not categorize Asian Americans as “underrepresented minorities.”10 These institutional policies mirrored the national perception of Asian Americans as model minorities, a stereotype that assumes Asian Americans are academically and financially well-off compared to other racial groups and do not need additionally academic, financial, and social assistance.22 Because of this perception, IUB Asian Americans were ineligible to apply to specialized programs aimed at financially, academically, and socially assisting minorities.

Not only were they excluded from minority-serving scholars and programs, Asian Americans had no institutional support system in place to address their needs and concerns.10 Despite, being the fastest growing racial group on campus in during the 1990s, Asian American students did not have any administrative representation--an Asian American advocacy dean--that addressed their academic and social needs as well as helping them navigate through bureaucratic “red tape”23 when they experienced prejudice and discrimination. In addition, IUB offered little Asian American cultural programs and no academic courses that helped Asian American students learn about Asian American history, literature, and political identity.24 This lack of cultural programming hindered Asian American students in responding to prejudice and discrimination that they frequently experienced. As a result, many racial incidents were not reported to the institution thereby upholding a culture of political passivity among Asian Americans. The exclusion of Asian Americans in minority programming, the absence of an Asian American advocacy dean, and university-led cultural initiatives culminated with the Asian American student population declaring that they were “neglected and excluded”24 by the university.

The Model Minority Myth and Exclusionary Policies at IUB

Asian Americans have been type casted as “model minorities” since the Reconstruction era when journalists praised Chinese immigrants for their obedience and industriousness than Southern freed slaves and Northern Irish immigrants.22 In the height of the Civil Rights Movement, the model minority image reemerged in the 1960s touting the educational and professional success of Japanese Americans despite a history of racist oppression and wartime incarceration.22 For decades, popular media perpetuated this image of Asian Americans as model minorities, which in turn removed them from minority status in national and regional policies.22

In 1992, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights conducted a study to investigate and heighten public awareness of the broad range of civil rights issues facing Asian Americans. Americans believed that Asian Americans were not discriminated against in the U.S. because of the widely held image that they are hardworking, intelligent and academically successful model minorities.25 The report contrasted this national belief and revealed evidence that Asian Americans faced widespread prejudice, discrimination, and barriers to equal opportunity in multiple sectors including housing, employment, and education.25 Within higher education, Asian Americans faced a number of discriminatory practices including unfair admissions policies, inequitable awarding of financial aid, underrepresentation of Asian American faculty and administrators, and failure of colleges to incorporate the experiences and contributions of Asian Americans in the mainstream curriculum.25

Asian Americans face inconsistent status as nonminorities in higher education

A prominent civil rights issue that Asian Americans faced was their inconsistent status as nonminorities in higher education. Examining admissions policy shifts revealed how Asian Americans have been “de-minoritized”22 over time through their establishment of minorities in the 1960s during the Civil Rights Era and their subsequent removal in the 1980s. The most prominent example is the Regents of the University of California v. Bakke case that scrutinized Asian Americans’ minority status within the University of California system.22 Among the CIC schools, depending on the institution and its policies, the university and its administrators had the liberty to define which racial groups were recognized as underrepresented minorities.78 Out of the 13 institutions in the CIC, Purdue University was the only one that recognized Asian Americans as underserved minorities.20 Five institutions, including IUB, did not categorize Asian Americans as underrepresented, and six institutions did not report a status.20

One of the reasons to why Asian American students were not categorized as underrepresented minorities was their significant proportional representation on-campus. University of Illinois Champaign administration specifically did not categorize Asian Americans students as underrepresented minorities because “their undergraduate percentage in the undergraduate population is above their respective percentages in the state population.”20 Institutions such as Northwestern University granted Asian American students as “ethnic” minorities but were not considered “underrepresented”20 minorities on campus.

Like its CIC peers, IUB had a similar policy for Asian American students. From 1975-1983, Asian American enrollment at IUB was the third highest minority population after African American and Latino American students.26 By 1984, Asian American student enrollment at IUB surpassed Latino American enrollment, placing Asian Americans as the second highest minority population on campus after African Americans.26 In 1990, despite being the second largest ethnic minority on the IUB campus24, the IUB administration did not consider Asian Americans as historically underrepresented minorities but rather as “over-represented in terms of the pool both at the faculty level and at the student level.”27

The Bloomington Faculty Council (BFC), an elective body that holds legislative authority in defining the admissions and retention of students on campus28, created a campus policy that determined minority status from state ethnic group statistics.29 “The issue was, if you look at the Asian American student population at the IU Bloomington campus, the representation was seen as high based on the percentage of Asians in the state,” said University of Libraries Dean James Neal who was also a member for the President’s Council for Minority Enhancement.10 For example, in 1990, Asian Americans accounted for 0.7 percent of the population in Indiana in the 1990 census, while Asian Americans account for 2.6 percent of the IUB student population.10 In 2001, the Asian American population rose to one percent of Indiana’s population, and Asian American students represented approximately 3 percent of IUB’s student population.29 With their on-campus percentage exceeding their state population percentage, IU administration determined that Asian American students were “not an area where the University needed to attract more students.”10

Since the 1970s, IUB developed numerous campus diversity initiatives to improve the campus’ racial climate including minority student and faculty recruitment and retention programs; Chancellor-appointed advocacy deans to represent specific minority groups; and cultural and academic centers to address minority concerns.30, 10 However, because their enrollment numbers were above the state population average, Asian Americans were ineligible for various IUB programs designed to financially, academically, and socially assist minority students.10 In addition, IUB administrators believed that Asian Americans did not need additional academic support. Dr. Herman Hudson, director and founder of one of IUB’s undergraduate minority scholarship—the Minority Achievers Program—said, “The Asian students that get to Indiana University, and even Asian students in high school, seem to be doing very well academically. Therefore, they, on the whole, do not need any special assistance as a group.”10 In 1994, Shirley Boardman, director of IUB’s affirmative action office explained that IUB’s minority programs and academic disciplines did not categorize Asian Americans as underrepresented minorities because they do not face the same social barriers as other minority groups. She affirmed that Asian Americans have the highest academic rankings and graduation rates among IUB minority groups and did not commonly face the same financial challenges in terms for paying for college.10

Over the years, IUB students wrote about the “blatant discrimination”23 of Asian Americans being excluded from minority scholarships both nationally and on campus because of the model minority stereotype. “Asian Americans do not receive one penny of this minority funding, because statistically, Asians are shown in some points to exceed the white majority in attaining the American dream,” said Phil Nguyen, an Asian American student. “Clearly, the American educational system works against Asians in labeling us a majority in one respect and then a minority in another respect.”23

Students also felt that IUB was assuming that all Asian Americans were highly motivated and successful and holding them to the “model minority image.”10 “By saying that Asians are overrepresented, by saying we don’t have any problems, by generalizing all of us as the ‘model minority,’ they’re ignoring some of the problems that do exist,” said Asian American student, Jules Lin10. Dean Alberto Torchinsky of IUB’s Latino’s Affairs Office, implied the model minority stereotype of Asian Americans might influence some IUB decisions regarding special programs for minorities. “Clearly, Asian Americans are perceived as successful. There’s a very positive stereotype of Asians. Consequently, there is very little sympathy for them when considering special programs.”10

Lack of Administrative Representation and Cultural Programming

This “over-represented minorities” status also extended to the recruitment of Asian American faculty members at IUB. In terms of IUB’s minority hiring practices and policies, the BFC policy defined “minorities” as African American, Latino, and Native American.31 In a 1985 BFC meeting, elected faculty members discussed proposals for a recruitment program to attract and retain African American, Hispanic, and Native American faculty members to IUB. Asian American faculty members were not included on the minority recruitment list despite being identified as one of the five racial groups under the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunities Commission (BFC, 1985, November 19). The BFC had decided that, “as a group of people they are not underrepresented on this campus. Therefore, it is questionable even on legal grounds whether we could take special means to recruit them.”32 In a 1992 report, the Affirmative Action Committee reported that out of the 1404 faculty on campus, 56 faculty identified as Asian, 45 as black, 19 as Hispanic, and two as Native American.33 Though Asian American faculty represented the largest racial group among faculty, they only constituted 3.9 percent of the total faculty population in this 1992 report. The majority of the faculty was predominantly white.

IUB’s situation was not in isolation as the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (1992) named the exclusion of Asian American in faculty and high-level administrator positions an overt discriminatory practice in higher education. This lack of Asian American faculty and administrative representation was apparent to IUB Asian American students, who were frustrated with the absence of Asian American role models and campus advocates.24 Since the mid-1970s, the IUB Latino and African American student populations had designated administrative liaisons called advocacy deans that represented their issues and concerns to campus administrators, faculty, staff, and community members.34, 35 The appointments of the Latino and Afro-American advocacy deans were crucial in the establishment of academic courses, resources such as periodicals, scholarships, culture centers, and cultural programming aimed at teaching and supporting their heritage.24

Despite, being the second largest minority group on campus in 1991, Asian American students did not have a designated Asian American advocacy dean.23, 24, 31 The lack of administrative representation resulted in mishandled racial incidents against Asian American students on campus. Two major racially motivated incidents against IUB Asian American students occurred on February and July 1990. The February 1990 case involved the Indiana University Police Department who unlawfully interrogated and harassed several IUB students whose names “sounded” Asian after a victim claimed that she was assaulted by an Asian male.24, 36 Two Asian American student organizations including the Asian American Association and the Indiana University Student Association Asian Affairs branch, lobbied the Indiana University Police Department for an apology, which was not given until almost a year after the incident.37

The July 1990 case involved David Jung, a Bloomington resident and IUB student, who was physically attacked and called racial slurs by two local teenagers. Following the attack, Jung reported the incident to the racial incidence team in the Dean of Students office but was not able to successfully try his two assailants.38 He also reported not telling his parents about the attack because he felt they would not understand.39 “My grandparents and my parents have experienced racism before, and I hesitate to tell my family about this because I don’t want to open old memories,” Jung said in The Bloomington Monthly Magazine.38 Jung believed having an Asian American advocacy dean would helped him navigate through IUB’s bureaucratic red tape and to ease with the cultural translation with his parents.39

These two racial incidents connected to a larger issue of the lack of educational opportunities for Asian Americans. IUB offered little Asian American cultural programs and no registered academic courses.24 This lack of any cultural and academic programming not only denied students to learn about their heritage, but it hindered Asian American students’ ability to recognize and fight against prejudice and discrimination.

In 1989, at the very first general mass meeting of the Asian American Association, the Dean of Students Michael Gordon called attention to the Asian American political passivity on campus.40 “On this campus, I have noticed that Asian-American students almost exist like the invisible man,” he said.40 He urged Asian American students to not pretend that racism does not exist for Asian Americans, reminding them of the internment camps in which thousands of U.S. citizens of Japanese descents were illegally placed during World War II. He urged them to stand up for their rights and to report racial incidents on campus.

Official racial incident reports collected by the IUB Racial Incidents Team also hinted at theAsian American political passivity. Out of 335 total racial incidents collected by the IUB Racial Incidents Team from September 1988 through June 1993, there were only 32 cases of racial incidents against Asian Americans reported to the university.41 Many more racial incidents went unreported.24 One reason was because Asian American students do not have a familiar figure of representation to support and guide them through racial incident reporting as demonstrated in the July 1990 David Jung case.24 In fact, racial reporting was a complicated and unclear matter at the university during the 1980s. If students wanted to officially report an incident with the university, they needed to file through multiple administrative offices and to their designated advocacy deans who represented their respective racial groups.42 With no Asian American advocacy dean to represent them and a complicated reporting structure, Asian Americans were discouraged to file a racial incident with the university.

Another reason was that Asian Americans were often easy targets of racism because of “a tradition of political inactivity and passiveness.”24 Some Asian American students reported that they were raised in a “tolerant culture”39 that did not report incidents of prejudice and racism. “Asians are very passive, they don’t want any trouble,” said Asian American student Joe Chen about the February 1990 Indiana University Police Department debacle.37 Asian Americans reported being frequently misidentified as a “foreigner” or lumped together as one monolithic Asian group, ignoring the historical and ethnic differences between the various Asian ethnic groups.39 Some Asian American students reported being called racial slurs such as “chink” from their classmates or from passing cars on campus.39 However, in many of these cases, Asian American students did not file these racial incidents with the university because of the perception that these racial slurs were not “extreme” enough to report.39 Asian Americans assumed that the term “chink” did not receive the same “outrage or reaction” as it would compared to racial slurs used against other minority groups.39 This culture of non-reporting upheld this Asian American political passivity and the model minority image but also prevented IUB administration to fully understand the racial climate experienced by Asian Americans on campus.

In an attempt to understand the racial climate for Asian Americans, faculty and students conducted surveys to capture Asian American students experience on campus. Over the years, the results were comparable to other minority groups on campus in which Asian Americans felt unsupported by the administration.30 In 1986, Professors Christine Bennett and Alton M. Okinaka conducted a study on IUB undergraduates and found that Asian Americans “often feel alienated from the rest of the student population.”24 In 1990-1991, then Asian American Association president, Mona Wu conducted her own survey of Asian American students on campus that affirmed that IUB administration needed to “increase their attention on Asian American concerns.”10 In 1991, Asian American student, Phil Sung, made a video documenting the stereotypes being imposed on Asian Americans on campus. “I found that all the people I interviewed felt a certain degree of alienation,” Sung said.39

In sum, IUB Asian American students during the 1980s through the 2000s realized that on both a local and national level, not only were they neglected and excluded, but also they felt completely “invisible”10 in the discussion of American race relations and institutional support at the IUB campus. Their feelings of being “alienated”24 among the student body and the IUB administration, as well as challenging the local and national discourse on race became the 20-year foundation of activism to form the AAS program at IUB.

Twenty years of Activism: IUB’s Asian American Social Movement

This social movement at IUB spans almost 20 years, and can be defined by three specific periods: 1990-1996 was community building through student-initiated programming; 1996-1999 was gaining support for the social movement outcomes through Asian pan-ethnicity and cross-racial collaboration; and 2000-2009 was the deradicalization of the social movement outcomes. Asian American activists is a term that I use throughout this paper because it is the most inclusive term for everyone who advocated for an AAS program. In the beginning of the social movement, student activists (both Asian Americans and non-Asian Americans) created a unified pan-ethnic community and defined their four major goals: (1) there should be an advocacy dean for Asian American Affairs; (2) there should be an Asian American Culture Center; (3) there should be an expansion in the library holding dealing with Asian American topics; and (4) there should be more courses available dealing with Asian American experiences (BFC, 1991, April, 16). Along the way, these student activists found allies and supporters among the ranks of faculty and administrators. Thus, Asian American activists include students, faculty, and staff as all of them have an impact and influence on helping the achievement of the outcomes of the social movement.

1990-1996: Building “Asian American Consciousness”

From 1990-1996, the social movement started by student-initiated cultural programming to combat the institutional exclusion and Asian American political passivity. The university offered little to no academic courses and designated space (such as cultural centers), cultural programming, resources or literature focused on the Asian American population and issues. In a student government proposal, Asian American students declared that there were “no opportunities for Asian American students to gain selfdiscovery and pride in their heritage.”24 Moreover, Asian American students at IUB did not have any ties to the outside community. Thus, they could not rely on ethnic and political organizations to teach them about Asian American consciousness and political strategies that activists had during the Third World Strike of 1968-1969.

This period of the social movement is characteristically student-driven with few Asian American faculty to guide them. Rather it was a small group of Asian American students who fundraised, organized, and ran these social, cultural, and academic programs. Retrospectively, coordinating student activities and events seems “common” in today’s standards of student organizations and programming.43 However, to this small group of Asian American activists, these series of events were important to them because the campus had never seen or experienced a coordinated set of activities solely dedicated to Asian American awareness and education.43 Furthermore, these series of cultural programming were in essence, “students teaching themselves”43 about their own racial history and how to advocate for themselves in the IUB administration.

Asian American activists at IUB taught themselves about history and advocacy

Because IUB offered little to no institutional support for Asian American students, students created their own community first through the founding of their own student organizations. Within their student organizations, Asian American students created their own cultural programming that focused on their educating the campus and themselves about Asian American history, issues, and the “Asian American consciousness,” which is described as a political and ideological identity that affirms the culture, history, and set of Asian American experiences within the U.S. racial structure.21, 43 Coupled with student-initiated programming, Asian American activists began to publicly voice their opinions in the student newspaper, The Indiana Daily Student, and alternate student-published periodicals. They used these platforms to defend themselves against Asian American stereotypes as well as their exclusion from campus racial discussions, minority programming and funding. As a result of this student-initiated cultural programming, Asian American activists created a rich and complex community network that provided the necessary momentum to advocate for their social movement goals of an AAS program.

Student-Initiated Cultural Programming

With Asian American students feeling alienated, neglected, and excluded by the IUB administration, they created their own student organizations that focused on Asian American and ethnic Asian concerns. Asian American organizations that welcomed students, faculty, and staff from all Asian ethnicities included the Asian American Association and the Asian Student Union (AAA, Fall Recruiting Brochure, 1994). One particular example is the founding of the Asian American Association which was established in 1987 with a goal to enhance “campus awareness of Asian American issues such as stereotyping, discrimination, and exploitation.”44 Ethnic Asian student organizations included the Chinese Student Association, Filipino American Student Association, Japanese American Student Association, Vietnamese Student Association, Korean American Student Association, Thai Student Association, and the Indian Student Association. There was also one Asian interest sorority, Kappa Delta Gamma. In total there were 19 Asian American and ethnic Asian student organizations at IUB forming an Asian American community or subculture.

Within campus environment research, subcultures are defined as distinct systems that are formed by a subset of members. These subcultures consist of norms, beliefs, values, and assumptions that are different than the dominant culture of the university.45 Subcultures can include fraternities and sororities, academic studies programs, and ethnic student organizations.45 Research on subcultures also suggest that these spaces serve as a space for identity development and cultivation of Asian American activism.45, 46, 47 Evidence also suggests that these subcultures provided a safe haven for Asian Americans to escape from campus racism and to discuss issues of race.48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53 Thus, IUB’s 19 Asian American student organizations not only provided a natural space for students to learn about Asian American identity, but it also was the root of their activism.

IUB's 19 Asian American student organizations were the root of activism

Socially, these student organizations initiated a network of informal and formal activities to learn about their political consciousness, educate the greater IUB population about Asian American issues, and to advocate for their social movement outcomes. Informal activities were the foundation of building a cohesive and unified Asian American community. These social activities included mass general meetings, creative coffee hours, organized dances, sporting events (such as tennis or volleyball tournaments), and potluck dinners to bring together different ethnic Asian groups and minority groups to “create a fellowship between students of ethnicity and race.”36 These informal activities allowed for a space for inter-ethnic Asian friendships to grow, which would eventually build towards a pan-ethnic Asian American community that could rally behind their four social movement outcomes.

Asian American activists also organized formal activities during this period that included academic programming to help them learn about their racial history and to educate the campus about Asian American issues. Asian American student organizations hosted discussion panels and group film watches to examine Asian American stereotypes and current issues.54 These organizations also brought in cultural speakers such as Gary Okihiro, one of the founders of the fields of AAS and comparative ethnic studies, to help enhance campus awareness of Asian cultures while teaching members about their own heritage. Student organizations such as the Asian American Association created and even curated their own Asian American literature. For example, the Asian American Association wrote and self-published newsletters named Bridging the Gap. Written by Asian American members, the newsletter publicized club events and editorials on current Asian American issues.54 The club even had a designed executive leadership officer, the Librarian, who curated their own library of Asian American books and magazines.54

One of the most important academic and cultural event was the Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, which first started in 1994. Entirely student-run, this month of events were particularly important because it was one of the first large-scale and coordinated events that brought the multiple Asian student organizations together to enhance campus awareness of Asian American issues as well as promoting cultural understanding among all ethnic groups.55 “There hasn’t been enough awareness of Asian American issues because Asian Americans are considered the ‘model minority,’” said Jules Lin, the 1993-1994 president of the Asian American Association.55 Lin is credited for conceptualizing the Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month because of his institutional savviness.43 “He was very well connected and understood how the campus works,” Ellen Wu said, an Asian American Executive Officer and current IUB history professor.43 Lin knew how to find funding within the student government, academic departments, and student affairs divisions. He also knew the importance of collaborating with other student organizations to coordinate such a large-scale event. The Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month was a public statement to the IUB administration and the campus to recognize Asian Americans’ invisibility at the university and as a way to reclaim their de-minoritized status.

The first Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month featured small and large cultural events. Smaller events such as their coffee hours focused on Asian American issues such as providing alternative representations of the model minority stereotype. Asian American students read poetry, performed skits, and played musical instruments to challenge the one-dimensional stereotype that Asian Americans only study medicine and science.10 One of their largest events was the Taste of Asia, which was a food festival and Asian American performance showcase. Eight Asian American student organizations collaborated to publicize, cook food, and choreograph traditional as well as modern dances.55 The first Taste of Asia, in 1994, drew more than 1,000 IUB students, faculty, and staff.55

Another poignant large-scale event at the first Heritage Month was inviting the Here and Now Acting Troupe to perform on campus. The collegiate, 14 member Los Angeles-based Asian American troupe drew nearly 400 students to the show.43 The event was particularly important because it was one of the first times where IUB students publicly learned about “social issues surrounding the Asian American community and revealed problems of cultural ignorance, prejudice, stereotyping, and racism.”56 Light-hearted skits poked fun at Asian American stereotypes, interracial dating, and cultural communication issues between parents and children. Serious skits depicted racism and hate crimes such as the reenactment of the 1982 Vincent Chin murder and the “Christmas Carol” style skit on the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre.56 One particular skit showed the ethnic division and violence that existed among the various Asian communities in the U.S. The skits “reminded the various ethnic groups that if they perpetuate racism among their own societies, tackling racism among all ethnic groups could not be possible.”56 Overall, the acting troupe created a sense of solidarity between Asian Americans at IUB and across the nation that they were not alone in experiencing prejudice and discrimination.

The success of the first Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage month in 1994 prompted student organizations to make it an annual tradition. The second and third Heritage Month, in 1995 and 1996 respectively, drew more than 2000 IUB students, faculty, and staff.57 The fourth Heritage Month in 1997 garnered almost $7,000 in funding and administrative support from the student government, the Indiana University Student Association.58 Even the IUB administration started to take notice. By third annual Heritage Month By the third annual Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, the IUB administration and faculty took notice. IUB President Myles Brand appeared at the third Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month to make a brief speech. “I am pleased we are gathered to celebrate the Asian Americans who play a big part in the University,” the President said. “Asian Americans add so much to the community and the University.”59 Asian American Association president and student, Christine Hsu, welcomed the presence of IUB administration at the Heritage Month, “This is a sign that faculty is taking an interest and that (Asian-American) awareness on campus is growing.”

Aside from creating their own cultural programming, Asian American activists also learned about their political consciousness and history through a decentralized, small network of courses offered by Asian American graduate instructors within traditional academic disciplines. For example, in 1993, Yuko Kirohashi, a history graduate student instructor taught an Introduction to Asian American Studies course through the Collins Living and Learning Center, a residential hall that allowed graduate instructors to propose and teach specialized courses that were not typically offered on the university’s official academic bulletin.43 Kirohashi’s course was the first time students (both Asian and non-Asian) critically examined highly-charged racial issues such as the 1982 racially-motivated murder of Vincent Chin by two white men who blamed him for the loss of American autoworker jobs and the important role that Korean Americans had in the interracial conflict during the 1992 Los Angeles Riots.43 Two other Asian American literature courses were offered in the early 1990s. One was taught by English graduate student instructor, Yuan Shu, through the Collins Living and Learning Center. The second course focused on Chinese American literature and was taught by Eugene Eoyang, a faculty member in the Comparative Literature department as well as the advisor for the Asian American Association.43

Practicing Political Advocacy and Raising Awareness of Asian American Issues

Coupled with student-initiated programming and courses, Asian American activists began to publicly voice their opinions against the invisibility of Asian Americans on campus and their exclusion from institutional policies through campus publications. Asian American activists wrote feature stories focused on Asian American prejudice and discrimination in the campus student newspaper, The Indiana Daily Student, as well as griot and Kiosk, which were student-published activist periodicals that covered issues that were “either ignored or superficially covered by the mainstream media.”60 Some Asian American activists wrote Letters to the Editors to the student newspaper, The Indiana Daily Student, expressing their frustration of Asian Americans being excluded in articles addressing minority students.

We are writing to express our disappointment at the manner in which minority issues have been covered in the Daily Student during the past few semesters…Other articles in the past have discussed such topics as minority enrollment, retention, and the GROUPS* programs with no mention of the Asian, Asian American, and Native American student population.61

*The GROUPS Scholars program is a minority serving scholars program that provides academic, financial, and social support to selected underrepresented Indiana resident college students. It was first established in 1968 to address low college attendance rates among underrepresented students at IUB.

Other students wrote Opinion Editorial pieces in the student newspaper addressing their experiences of not being allowed to apply for minority programming and funding. “This kind of discrimination on the basis of race is, by definition, racism,” Michael Huang wrote in a 1997 opinion piece in the student newspaper, The Indiana Daily Student.62 He urged IUB administrators to reform their policies to allow Asian American students to apply.

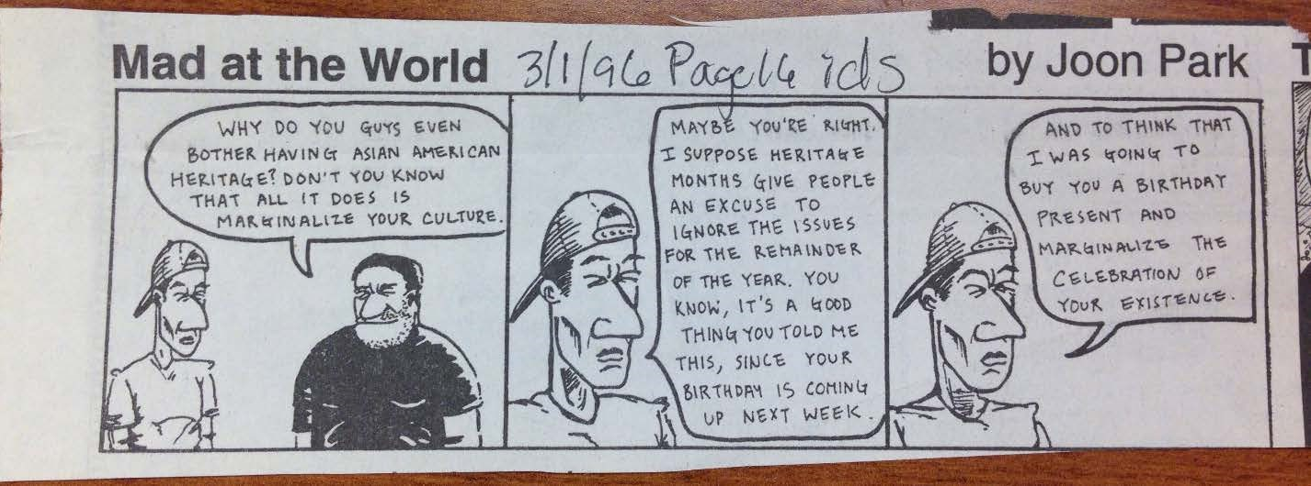

Others such as Asian American student and 1995-1996 president of the Asian American Association, Joon Park, voiced their political identity artistically. Adeptly titled, “Mad at the World” Park published a series of comic strips in the Indiana Daily Student that cleverly served a dual purpose.63 His comic series jabbed at the Asian American stereotypes that students faced on campus while publicizing upcoming Asian American student-run programming such as the Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

Comic by Joon Park, Indiana Daily Student, March 1, 1996, p. 16.

From 1990-1996, these 19 Asian American student organizations and sorority served as an emerging community that took initiative to create their own cultural and academic programming when the university had none. Their student-initiated programming seemed to be successful drawing hundreds sometimes thousands of IUB students, faculty, staff, and community members to their events.61 Asian American students started to become more active in voicing their opinions about Asian American stereotypes that excluded them from minority issues and specialized programs.

Despite their success of initiating their own programming, academic courses, and publications, Asian American activists realized that they needed stability and permanence in the IUB Asian American community. They recognized that student leadership within the student organizations changed yearly. Upperclassmen with the historical knowledge of past Asian American activist efforts and the institutional savvy eventually graduated, and incoming freshmen and sophomores had to redouble their advocacy efforts again.

The student organizations also had a few advocates among the faculty and staff who supported their advocacy efforts. Those among them were Steven Yee, a staff member at the International Center; Kenneth Rogers, Dean of International Services; and Professor Eugene Eoyang, a professor in Comparative Literature and advisor to the Asian American Association. However, Asian American activists recognized that their advocacy efforts needed to go beyond themselves. Thus, the next period marks the second phase of the AAS movement where multiple Asian American student organizations unified into a pan-ethnic effort. In addition, they combined with multi-racial groups to gain critical mass to officially push for their social movement goals: An Asian American advocacy dean, an Asian culture center, and an AAS program.

1996-1999: Gaining Critical Mass through Asian Pan-Ethnicity and Cross-Racial Collaborations

The period of 1996 to 1999 focused on gaining a critical mass to navigate institutional racism within a complex university administration. IUB Asian American activists formed multi-level and crossracial alliances within other ethnic Asian student groups as well as student groups such as the student government who had direct ties (or at least a platform to talk) to campus decision makers. IUB’s own social movement was also aided by a national shift of multiculturalism and the second wave of Asian American social movements advocating for ethnic studies within the university curriculum. In the mid-1990s, students and faculty across the nation began to demand for inclusive histories within the traditional American narrative covered in universities’ curriculums.64 Across the nation’s universities, there was an increase in multi-racial student activism demanding ethnic studies programs.

IUB administration were also drawn by nationwide media coverage of 1995-1996 ethnic studies strikes at Princeton, Columbia, and Northwestern University. In April 1995, students at Princeton University staged a 36-hour sit-in at the university president’s office demanding an Asian American and Latino Studies program.15 Also in April 1995, Northwestern Asian American activists went on a multi-day hunger strike after the administration rejected a 200-page proposal for an Asian American Studies program.15, 65 In April 1996, a multi-racial coalition of activists at Columbia University went on a multiday hunger strike and took over university buildings to demand an ethnic studies department.15

Asian American activists at IUB followed a similar path of tactics as these national social movements. They gained critical mass of support by unifying the Asian American community and creating strategic relationships with multi-racial student organizations. With a larger critical mass of supporters, Asian American activists were able to draw attention from IUB administrators to seriously consider their demands.

Asian American Pan-Ethnicity at IUB

In 1990-1991, there was a short-lived social movement to rally for a designated cultural center and an advocacy dean led by Mona Wu, then president of the Asian American Association student organization, and two other members. They wrote and interviewed IUB administrators, gathered statistics, and distributed surveys to Asian American students asking if they felt discriminated on campus and if they would support the hiring of an advocacy dean.10 They submitted preliminary proposals to several faculty committees. However, a formal proposal was never submitted to the Bloomington Faculty Council because IUB was facing a “significant budgetary problem” due to state appropriation cuts.66 In addition, there was not enough critical mass and desire from the members of the Asian American community that time.66

The social movement failed not only because of timing, but it could not gather enough support for the social movement outcomes. “I did not feel the rest of the Asian-American population were going to support us,” Wu said.10 Ethnic differences were one of the reasons for the small support basis with the Asian American community for an advocacy dean. “I am Chinese American…Perhaps Asian American students felt I’m just out for a Chinese-American advocacy dean,” Wu said.39 With over 18 Asian and ethnic-Asian student organizations on campus with different agendas and concerns, they had not yet found common issues to unify around.

Asian American activists did not undertake the social movement outcomes again until 1996 when student organizations shifted towards an Asian American pan-ethnic outlook. Pan-ethnicity is when different ethnic groups merge into a common culture as a means to increase political and social power when faced with racial discrimination.67, 68 A national example of Asian American pan-ethnicity is the Third World Strike of 1968-1969 when various Asian ethnic groups lobbied together for an AAS program. Similarly, the IUB pan-ethnic Asian American identity was founded because the various student organizations banded together to fight against stereotypes and misconceptions by collaborating on informal and formal activities established from 1990 through 1996.69 In a 1996 grant application for student activities, members of the Asian American Association voice their interest to collaborate with other ethnic Asian student groups.

There has not been much cooperation or communication between the different IUB Asian and Asian American student groups in the past. However, we have seen that in the past, our collaborative efforts have drawn very positive responses from the IU community, during Asian American Heritage Month, for example, the event that is most well attended is the one in which all the groups have worked together. We want to continue to contribute to the IU community as a group.69

Those six years of collaborating on events strengthened friendships but also sparked a unified political identity, something that was missing in the failed 1990-1991 social movement.

This pan-ethnic identity was solidified in 1995 when several members of the Japanese and Indonesian Student Associations planned the campus’s first “Asian Unity Night,” which was a food festival, cultural show, and team building exercises.70 The impetus was not only to encourage camaraderie among the student organizations but “to show that each of the student groups sometimes face the same kind of problems and can work together for a solution.”70 The Asian Unity Night sparked interest in creating a student union that increased communication, interaction, and “coordinated the political agenda” for the different Asian and Asian American groups on campus.71 In 1996, students from the various 18 Asian American and ethnic-Asian student organizations formed the Asian Student Union to provide “a unified voice to inform administrators about emerging cultural concerns” (Carothers, 1996, September 26, p. 1). Specifically, the Asian Student Union aimed to organize student efforts to achieve long-term social movement goals that had originally failed in 1990 and 1991. “This is all driven by student activism,” Truong said. “We all have to the drive to work together. As long as we have interested students, we can overcome any challenges.”70

To gain support for the Asian American community’s social movement outcomes, the Asian Student Union with seven other student organizations won the bid to host the 1996 Midwestern Asian American Students Union Conference, an organization consisting of 20 Midwest universities that began in response to a need for political unity among Midwest Asian American students.72 Hosting this fourday conference was important because not only solidified pan-ethnic efforts at IUB, but it drew regional and institutional attention to IUB’s social movement outcomes.

In hosting this conference, dedicated students at IU are making a statement that Asians and Asian Americans are a unified community. We are working to make positive changes such as establishing an Asian culture center and an Asian American studies program. These changes are mutually beneficial to academic institutions and to the community as a whole.73

Drawing nearly 400 attendees from 25 Midwestern public and private universities, the IUB Asian American community demonstrated to the IUB administration that they had a unified Asian American community and the support of a regional body of Asian American activists.74 The four-day conference ended with a full-day fast and candlelight vigil to recognize IUB’s social movement alongside the nationwide movements for an ethnic studies program that occurred in at Princeton (1995), Northwestern (1995), and Columbia University (1996).65 Unlike the failed 1990-1991 social movement, the IUB Asian American activists finally had enough critical mass and “political power”75 to finally push forward, under a now unified pan-ethnic voice, with their outcomes.

Cross-Racial Collaboration at IUB

Evidence also suggests that cross-racial collaboration aided Asian American activists in fulfilling their social movement outcomes. Asian American activists did this by recognizing that other minority student groups had similar social movement goals. They were all demanding attention from the IUB administration to instigate reforms on campus that included creating academic and social places on campus that represented and served minority students’ identity, histories, and needs. Thus, Asian American activists combined their social movement goals with other minority groups on campus to present a unified agenda to IUB administration. Gaining support from other minority groups helped focus the IUB administration’s attention on Asian American concerns as well.76

On April 24, 1996, IUB Asian American activists united with four other student organizations--the Black Student Union, Latinos Unidos, griot, Conscious Oppressed Unified Peoples, and the Indiana University Student Association--to call attention to IUB’s minority students.77 Specifically, they united their social outcomes goals into a three part-proposal that recommended restructuring IUB’s Office of Afro-American Affairs; establishing an Asian American advocacy dean and Asian Culture Center; and creating a Latino Studies Department. The proposals were sent to a faculty committee focused on strategic directions.77 “I think it’s important to come together as minority students and voice our concerns,” Maki Fukasaku said, an Asian American activist and student said.77 Garnering support from other minority groups will help focus attention on Asian American students’ concerns. “Right now there is a lot of momentum on campus within the Asian American community,” Nicole Lee, a member of the multi-cultural coalition said. “Until now, we haven’t had a coalition of minority students on campus.”77

This network of cross-racial collaboration serendipitously developed when forming the Asian American sorority, Kappa Delta Gamma.43 The idea to form an Asian American sorority began in 1993 by Christine Hsu and Ellen Wu, who wanted a sorority that would focus on the culture experiences of Asians and Asian Americans in the Midwest.78 During the three year process forming the sorority, Wu and Hsu worked more closely with students from other groups. As part of the governance structure at IUB, to be an officially recognized sorority, a new sorority needed to be part of a Greek Council. There were three existing Greek Councils on campus that represented mainstream fraternities and sororities as well as well-established African American Greek houses. However, Wu felt that the new Asian interest sorority did not fit under the mission of three existing Greek Councils.43 Together with representatives from a Latina sorority and African American fraternity, Wu created a multicultural Greek council to house these new Greek chapters. It was through this process as well as her time working on the student newspaper where she met representatives from other minority student groups who were advocating parallel demands as Asian American activists. Historically, Asian Americans did not reach out to these student groups but the timing was right. All of their social movement goals were similar such that they wanted IUB administration to make reforms to make the campus more welcoming for students of color.

Student groups called for reforms to make the campus more welcoming for students of color

Asian American activists also extended their cross-racial efforts to the Indiana University Student Association, the student government body that advocated student ideas to IUB’s highest levels of faculty and administrative decision-making.79 This strategic relationship with the student government is both financial and political. The student government body was the main organization that divided student fees, collected from tuition, to provide funding for the hundreds of student organizations on campus. In addition, Indiana University Student Association, particularly the President of the student body, have representatives sitting on the Bloomington Faculty Council as well as other administrative and faculty committees. Because of its direct channels to campus decision-makers, a relationship with the Indiana University Student Association was a political one as well.

For Asian American activists, their relationship with the student government started as early as 1991. The student government was one of the Asian American activists’ first political advocates. From 1990-1991, Indiana University Student Government passed multiple proposals to support an Asian American advocacy dean and brought the proposals to the attention of the Bloomington Faculty Council.10 The student government also provided much needed funding to support the first Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month in 1994. The Indiana University Student Association agreed to fund the project because the organization believed its role in increasing cultural awareness. “It’s keeping with our policy to support ethnical functions and awareness-raising projects,” 1993-1994 Indiana University Student Association President Jay Fultz said.80

However, not all student government cabinets supported the diverse needs of the student population. In 1996, a number of student organizations including Kappa Gamma Delta, IUB’s Asian American interest sorority, the Asian Student Union, the Asian American Association, the Black Student Union, Latinos Unidos, griot, Conscious Oppressed Unified Peoples demonstrated their political power and critical mass by influencing the 1996 student body presidential election. These minority group leaders critiqued the current cabinet and student government president for carrying a “stigma of exclusion”76 and not actively seeking out different opinions including those of minority students who were demanding reforms and changes on campus. The group of minority leaders rallied and endorsed the student body presidential ticket of Moats-Moor-Skomp-Bhimani, who would bring “radical change”76 and represent the interests of minority student organizations including those of Asian American activists to get administrative representation, a culture center, and an academic program.

With the help of these minority leaders and other student groups on campus, the Moats-Moor-Skomp-Bhimani presidential ticket won the 1996-1997 academic year. This win was particularly important for the multi-cultural coalition’s agenda because they needed the voice and position of the student government to bring their agenda to the attention of the IUB administration. They also wanted a student body president and the cabinet to represent the interest of the minority student populations on campus. Following the 1996 student body election, the Moats-Moor-Skomp-Bhimani upheld their promise. On July 19th, 1996, they endorsed a formal proposal for the multi-cultural coalition’s demands of an Asian American advocacy dean, cultural center, and an academic program. The formal proposal was submitted to the Bloomington Faculty Council in fall 1996.

A Large Victory for the Asian American Community

The Bloomington Faculty Council considered the proposal that semester, and in January 1997, the Asian American community gained a large victory on their agenda. Thanks to the persistence of the Asian American community and the multi-cultural student coalition, the IUB administration granted $50,000 to create an Asian cultural center on campus.81, 82 However, the Bloomington Faculty Council tabled the Asian American advocacy dean initiative until fall 1997 because, according to university governance policy, students could not lobby for such a high-level position that held a dual tenure-track and administrative appointment.81, 82 The request needed to come from faculty.83 With written support from IUB administration, the 1996-1998 president of AAA, Joon Park, convinced several faculty members to write letters of support asking the Bloomington Faculty Council to place the Asian American advocacy dean on its agenda.84

However, in fall 1997, the Budgetary Affairs Committee, one of the largest Bloomington Faculty Council advisory committees, rejected the Asian American advocacy dean initiative because “members of the committee had reservations about the effectiveness of advocacy deans.”82 The advocacy dean governance model failed to hold enough authority within the IUB administration to accomplish campus diversity goals.82 “Unfortunately, advocacy deans have become more of IU’s moral conscious than an authority figure,” then Dean of Latino Affairs Alberto Torchinsky said.82 Furthermore, due to the limited budget, the advocacy deans had no support staff to help with the various responsibilities. “We are expected to be the dean of students, dean of faculties, affirmative action officer, and a representative of the community all wrapped into one” then Afro-American Dean Lawrence Hanks said.82

Nevertheless, with the creation of an Asian cultural center on campus, Asian American students not only had their own physical space but also gained a permanent administrator to represent them.82 In spring 1999, IUB hired Melanie Castillo-Cullather to be the director of the newly created space, formally called the Asian Culture Center. Together with the Asian American community, they began to advocate for the next item on the Asian American agenda: an AAS program.

2000-2009: Deradicalization of Asian American Studies

During this period, activists needed to understand and play by the rules of the university administration to achieve their goal of creating an AAS program. Activists targeted key decision makers such as university executive leaders in the IUB administration and curriculum approval committees to understand program development policies. Activists also formed cross-racial collaborations with already existing ethnic studies on campus to share knowledge on policies, procedures, budgeting, and advocacy within higher education. They engaged in regional benchmarking with AAS programs at peer institutions in the Midwest to share resources such as successful academic proposals and budgeting documents.6 Asian Americans activists attended CIC meetings to collect information on how other AAS programs developed. When developing the proposal, current and former directors of AAS programs at other Big Ten universities shared their experiences and gave valuable comments on IUB’s proposal. These methods helped form a critical mass of activists both within and outside the small Asian American population at IUB.

Activists marketed Asian American Studies as an interdisciplinary program for all students